Timing Silage Harvest

Originally written August 20, 2014. Last updated

August 25, 2016

Corn must be ensiled at the proper moisture to get fermentation for preservation. But, determining when to harvest corn at the right whole plant moisture is difficult. Each storage structure properly ensiles at slightly different

plant moisture optimums. Harvesting corn too wet for the storage

structure will result in reduced yield, souring and seepage of the

ensilage, and low intake by dairy cows. Harvesting too dry reduces

yield, can cause mold to develop, and lowers digestibility, protein and

vitamins A and E.

Kernel milk is not a reliable guide for timing silage harvest

Dry matter content of whole plant corn varies with maturity. The position of the kernel milk-line is not a

reliable indicator for determining harvest timing. Geographic location,

planting date, hybrid selection, and weather conditions affect the

relationship between kernel milk-line position and whole plant dry

matter content.

Determining field harvest order and initial plant sampling

The first step to determine when a field is ready for harvest is to note the order in which you planted your fields. Next, note silking dates of the fields to project calendar days to when a field will mature. Once corn silks, approximately 55 to 60 days is required to achieve maturity at R6 or the

"black layer" stage (Abendroth et al., 2011). Development during grain filling is influenced by temperature, but not as much as during the vegetative leaf emergence stages. Instead the number of days between pollination and a killing frost influence the time to maturity. So if an average killing frost occurs October 1, then subtracting 55 to 60 days means that the crop must be silking by August 2-7.

We know that kernel milk stage is not reliable for determining the

actual harvest date, but it is a useful indicator of when to sample

fields to measure plant dry matter. Silage harvest usually begins around 50% kernel milk which is 42 to 47 days after silking, so silking must occur by August 15-20

in order to mature before typical killing frost dates; but remember that the timing of silage harvest is dependent upon achieving the proper moisture for the storage structure (Table 1).

Noting the order that fields silk will help plan the harvest queue of your

fields and scheduling of custom choppers.

|

Table 1. Kernel milk stage

"Triggers" for timing silage harvest

|

|

Silo Structure

|

Ideal Moisture Content

|

Kernel Milk Stage

"Trigger"

|

|

|

%

|

%

|

|

Horizontal bunker

|

70 to 65

|

80

|

|

Bag

|

70 to 60

|

80

|

|

Upright concrete stave

|

65 to 60

|

60

|

|

Upright oxygen limiting

|

50 to 60

|

40

|

|

"Trigger": kernel milk stage to begin checking silage moisture.

|

Determining Silage Moisture

The only reliable method of determining the optimal time to harvest corn

silage is to sample the crop and directly measure the % dry matter of

whole plants. This information combined with average whole plant

dry-down rates can be used to roughly predict the proper time to harvest

corn silage.

The next plant indicator that determines the order of fields to harvest is movement of the kernel milkline. Once kernel milkline begins to move, measure moisture of fields intended to be harvested for silage (Table 1).

Corn should be first sampled to measure dry matter shortly after full dent stage (80% kernel milk) for

bunker silos and bags, at 60% kernel milk for conventional tower silos, and

at 40% kernel milk for sealed (oxygen-limited) tower silos. It is

important to begin sampling early as a precaution against variation

in dry down. You will likely be too wet, but you will have an indication of how quickly drydown is occurring when the next sampling date takes place.

Sampling a field for whole plant moisture

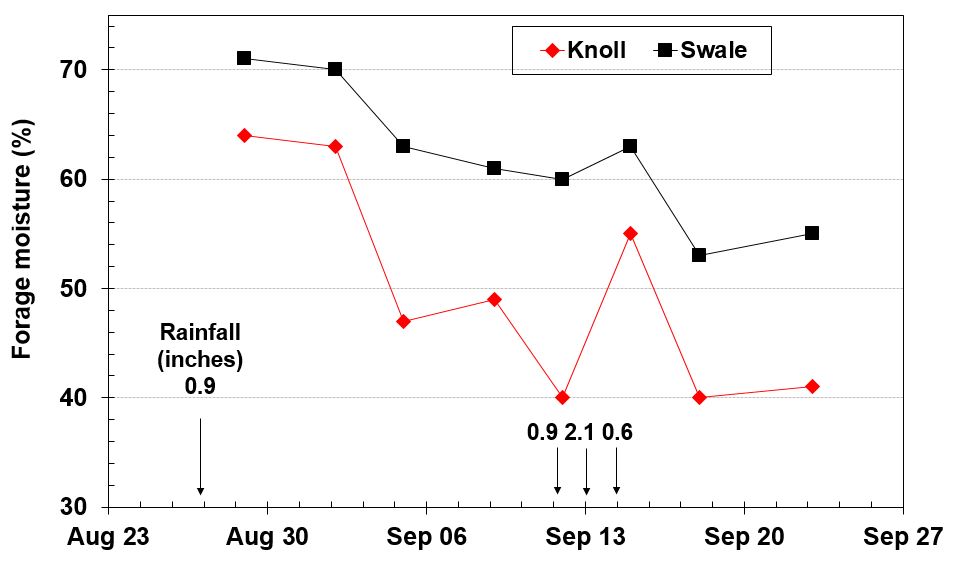

Ideally the field to be harvested is uniform in development, but the reality is that uniformity is rarely achieved. Separate uneven fields into representative groups. Figure 1 describes the moisture drydown patterns of two locations in the same field. Knoll areas were as much as 20% units different from swale areas.

Figure 1. Forage moisture of corn growing on a knoll and a swale at Arlington during 2003.

Sample two or more locations for each representative group in the field. Over time, sample the same locations

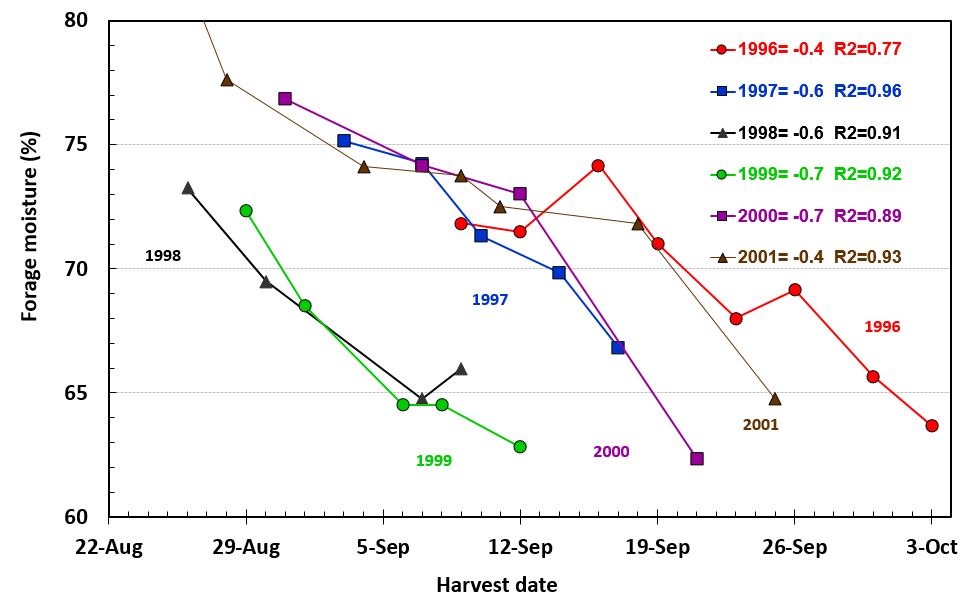

- trying to determine the rate of drydown. Scott Hendrickson (Manitowoc county agent) measured whole-plant moisture over time at three sites in the county by always returning to the same location in the field (Figure 2). Depending upon year the average drydown rate ranged from 0.4 to 0.7 percent per day.

Figure 2. Corn silage drydown during harvest (Hendrickson, Manitowoc County, WI)

Procedure for measuring plant moisture

1. Sample 3 to 5 plants in a row that are well bordered and representative.

2. Put in plastic bag,

3. Keep plants cool,

4. Chop as quickly as possible,

5. Measure moisture using NIR spectroscopy and/or by drying using a, Koster oven, microwave, or convection oven (Peters, 2000).

Predicting silage harvest date

Use 0.5% per day during September to predict the date when a field will be ready for the storage structure.

For example, if a given field measures 30% dry matter at the early

sampling date, and the target harvest dry matter is 35%, then the

field must gain an additional 5% units of dry matter, thus requiring

an estimated 10 days (5% units divided by 0.5 unit change per day). If weather is warm and dry, use a faster rate of drydown (1999 and 2000 in Figure 2). If weather is cool and wet, use a slower rate of drydown (1996 and 2001 in Figure 2). We are most interested in the rate of corn silage drydown. Wisconsin county agents have been accumulating corn silage drydown information since 1996. Results from county

"Drydown Days" can be checked at the website

http://fyi.uwex.edu/silagedrydown/ which averages and predicts area harvest dates.

This procedure provides only a rough estimate for the harvest

date. Many factors affect dry down rate, including hybrid, planting

date, general health of the crop, landscape position, soil type, and

weather conditions. In general, corn silage that is slightly too dry is worse

than corn silage that is slightly too wet. Therefore, starting harvest a

little early is usually better than waiting too long.

Abendroth, L.J., R.W. Elmore, M.J. Boyer, and S.K. Marlay. 2011. Corn

growth and development. PMR1009. Iowa State University.